PRESS RELEASE: KYND named among world’s most innovative AIFinTech companies by FinTech Global

Understand, manage and take control of your organisation’s cyber risks simply, quickly and cost effectively.

Sell and renew more cyber insurance policies, and keep your clients happy with our tools and support.

Make better underwriting decisions by removing complexity and accessing instant insight into cyber risk exposure.

Get a clear, easy-to-understand view of cyber vulnerabilities and deliver real results for your clients.

Get a clear, easy-to-understand view of portfolio cyber risk vulnerabilities and minimise investment risk exposure.

By KYND

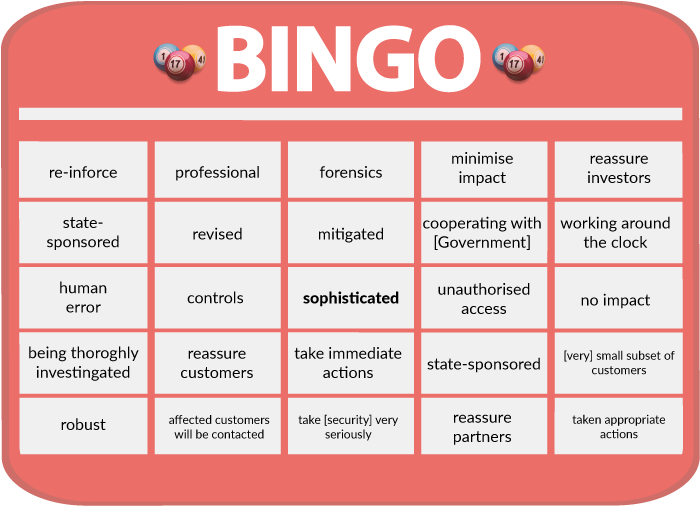

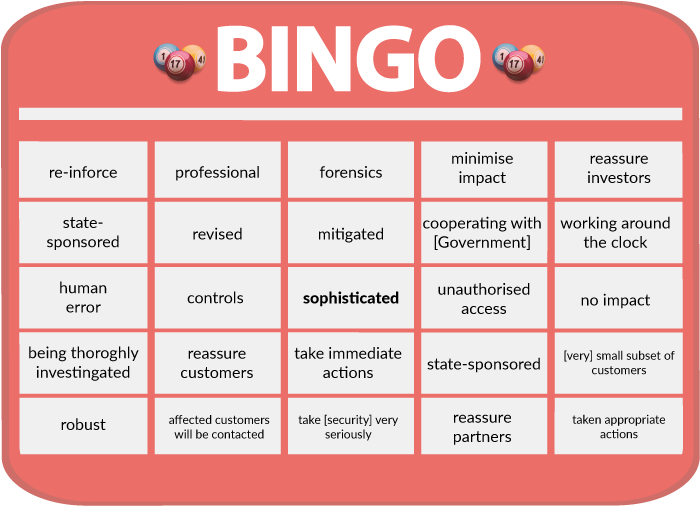

Google: "cyber incident statement". Look at a few results at random... Spot any patterns?

The free cell in our bingo scorecard for this must be the word "sophisticated".

When researching trends in "sophisticated cyber-attacks" mentions, I came across a Forbes article which follows exactly the approach I had in mind, from noting the over-use of the term to analysing a few memorable attacks which were characterised in such way only for later to be discovered that, actually, they involved traditional vectors. It also does a great job of exploring the reason for the initial characterisation.

Following on from that, I will try to explain why we at KYND tend to react with scepticism when we invariably spot the same pattern time after time.

The sophistication of cyberattacks is indeed on the rise. Microsoft reported this trend in 2019, and in 2020 we saw a great acceleration of that. Another interesting trend with some degree of overlap is that state-sponsored attacks are reportedly also on the rise.

We also know that overall volume of attacks and number of incidents has been steadily increasing, in many aspects, with help from the current health context as we wrote about in March last year, just when most countries were starting to get to grips with all of the implications of a global pandemic.

At KYND we have a privileged perspective over the cyber risk landscape as we monitor a growing number of organisations, currently in the thousands, and as such, have developed insight into what the average organisation's risk exposure looks like... Unfortunately, it's not a pretty picture!

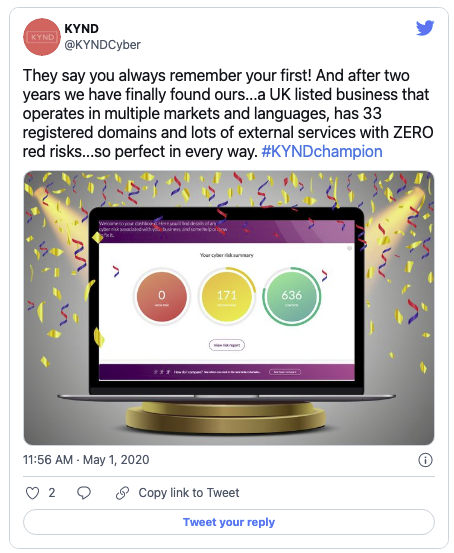

We have released a number of white papers focusing on different cohorts of organisations - Fraud and Cyber Vulnerabilities in the UK Legal Sector, Cyber vulnerabilities on AIM, Cyber risks in Independent Schools - which go into detail about their respective cyber risk profiles and areas in which they're particularly exposed, but nothing quite captures our sentiment like this tweet from Andy, our CEO, back in May:

Examples of RED risks as currently flagged by KYND include certificates issued by untrusted authorities, missing SPF or DMARC records, open database ports and out-of-date software. The knowledge of these is a great first step for any bad actor to plan and implement, respectively:

We wouldn't characterise any of these as particularly sophisticated, and a significant number of organisations which we monitor are at risk from at least one of these cyberattacks. Finding vulnerabilities often involves a fair level of technical sophistication however exploits are commoditised, and often publicly available.

Using another search example, this time with stock photography, "hackers" are depicted invariably as hooded men, coding away in the dark with the fluorescent green columns of glyphs from “The Matrix” scrolling in front of their eyes.

Hollywood, still the great moulder of perceptions of our age has a huge collection of absolutely ridiculous representations of "hacking" (with very few some notable exceptions, like "Mr. Robot").

The long-running crime forensics TV show “CSI” isn't exactly known for its realism - everyone remembers the magical "enhance" button that lets you take a low-resolution CCTV frame and identify the licence plate reflected in the eye of the victim, 200m away from the camera. As a software engineer, though, the first scene that comes to mind is this one.

With their vast team of actors, writers, directors, producers and assistants, you can only conclude that no one on the set flagged that it doesn't make any sense to "build a Visual Basic graphical interface to track an IP address"... You could, but why would you?!

Similar style of show, “NCIS”, features a world-first 2 people keyboard defence against a cyber attack, finally resolved by unplugging the monitor - you watch the video here.

A final notorious example, among many, is the 2001 star-studded blockbuster Swordfish.

The scene: Hugh Jackman with headphones on, smokes a cigarette in a dimly lit room while typing random characters looking at half a dozen screens... He gets more and more excited, bar a few brief moments of frustration. Eventually starts typing standing up, dancing, typing gibberish more frenetically until he finally cracks it: you can build a cube out of smaller cubes...

These scenes are unintentionally funny but only to a minority of viewers. Most people don't have any idea of what systems, processes, tools and techniques are actually involved in a cyber attack or data breach so these very creative, but still ridiculous portrayals, are perceived as plausible. When organisations publish statements minimising responsibility for leaking customer data, for example, they're taking advantage of this cyber illiteracy to defer responsibility.

In real life, an attacker may have a number of different profiles, from the script kiddy defacing websites to impress his friends using a few recipes he's picked up online, to professional cybercriminals, also using readily available tools and techniques to extort money from organisations or individuals via ransomware or phishing attacks, or security experts employed by nation-states to perform industrial or geopolitical espionage or even cyber-warfare, targeting the destruction or debilitation of their opponent's critical infrastructure or services.

The Stuxnet computer worm is a good example of the latter. First identified by antivirus software researchers in 2010, it's considered the first publicly known act of cyber-warfare. It is believed to have involved physically stealing private keys from secure locations in Taiwan and the utilisation of 4 zero-day exploits in multiple phases: travel on USB sticks, infecting Windows computers and targeting Siemens industrial controllers which were known to be used in an Iranian nuclear power plant to manage centrifuges, used for uranium enrichment, key for the country's nuclear program.

Once it identified it was running on the final target, it would sabotage the enrichment process and delay the Iranian nuclear plan by destroying centrifuges, causing them to rotate at unsafe speeds while reporting normal function. It would do this stealthily, so effectively that people lost their jobs because it was assumed employees were to blame.

There is an excellent documentary on this, very appropriately called Zero Days.

That's a good benchmark at the top end of the level of sophistication. On the other extreme, much more frequently, you have people using tools and techniques not too dissimilar to the ones KYND uses, to find victims.

Typically, targeted attacks may require a level of sophistication which is not really necessary if cybercriminals are casting a wide net.

If you cover the basics: provide cyber awareness training for your employees, enforce strong password policies and multi-factor authentication, the use of firewalls and anti-virus software, protect your email domains from spoofing and impersonation, reduce your attack surface by designing your networks to prevent direct external access to critical internal services and components, only expose services which are absolutely needed publicly and systematically and frequently patch your software, you will greatly reduce the likelihood of an attack, simply because you're not triggering any alarms. You can still be the target of a directed attack, which is rarer but non-negligible, but you'll be making your attackers' lives much more difficult.

One illustration that has always stuck with me has a cyber security professional represented as a gardener, raking leaves from his fragile wood-fenced backyard while a storm rages in the distance…

Just covering the basics is a never-ending process which requires persistence, commitment, and dedication. Just look at that initial search result for post-incident statements or to the list of leaks from HIBP… Sometimes it feels like it’s just a matter of time until the systems that you're responsible for get somehow compromised, but organisations have the obligation to their partners, customers, users, and investors to keep raking those leaves and patching that wooden fence.

If you do find yourself being the target at any point, we suggest you take full responsibility and take immediate remedial action while communicating clearly and openly what has occurred. We assume this also means avoiding faded jargon. As a good example of transparency and clarity in the face of an incident, have a look at how Norsk Hydro, a giant in the fields of materials and renewable energies, dealt with a ransomware attack.

They say the truth always comes out in the end - that’s certainly the case when we’re talking about public-facing internet infrastructure and services - it’s all there for everyone who’s looking, to find.

PRESS RELEASE: KYND named among world’s most innovative AIFinTech companies by FinTech Global

PRESS RELEASE: Talan chooses KYND to deliver advanced cyber risk intelligence to clients

PRESS RELEASE: KYND wins ‘InsurTech Innovation of the Year’ at InsuranceERM Americas Awards 2025

Accreditation & Features